The Gower Portrait (c1590)

Lettice Knollys was acutely conscious of her lineage and social standing, described by contemporaries as beautiful, elegant, proud, and ambitious. In the Tudor world, portraiture functioned not merely as likeness, but as visual rhetoric. Symbolism functioned as a sophisticated and widely understood language among the political and cultural elite. Allegory—rather than explicit declaration—was the preferred mode of expression, particularly when identity, succession, or royal proximity were sensitive matters.

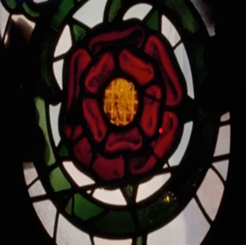

In Lettice’s widow’s portrait by George Gower (c. 1590) (above left), a red rose appears discreetly on her gown over her heart. This is a verifiable visual feature of the painting and was almost certainly included intentionally. The red rose had long been established as the emblem of the House of Lancaster (above center) and, following Henry VII’s victory in 1485 at Bosworth, became a central component of Tudor dynastic symbolism. While portraits of Henry VII, Queen Mary I, and Anne Boleyn depict those figures holding the red rose openly, Lettice adopted a more restrained approach by wearing the emblem rather than displaying it overtly. Although no contemporary explanation for the motif survives, its presence invites interpretation within the symbolic vocabulary of the Elizabethan court.

I suggest that Lettice deliberately selected this motif to signal what she believed to be her true ancestral descent from the House of Lancaster. As the daughter of Catherine Carey, Lettice would have likely been told of her true lineage and the vital importance of keeping that identity private. By the time this portrait was painted, Lettice had been widowed twice, most recently by the death of her second husband, Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester. She had been permanently excluded from court life and had little prospect of reconciliation with the queen. In this context, it is entirely plausible that Lettice felt she had little left to lose and chose to express—albeit subtly—her true identity—that she was the granddaughter of King Henry VIII.

Lord Denbeigh

We also see suggestive symbolism on her son, Lord Denbeigh’s, effigy (below). We can see on his coronet what I believe are roses rather than cinquefoils since they are rounded rather than pointed. Additionally, they cannot be forget-me-nots, since those traditionally appeared with a very different center (below right).

To me, this is telling, as roses would make sense for a child who was a Tudor and a great-grandson to Henry VIII. It is also of interest that Dudley and Lettice had a memorial and effigy made at all, as this was something that had not been seen in several hundred years, and even then, only for royal princes and princesses.

The Dudley-Knollys Tomb

We now go to the tomb and memorial of Lettice and her second husband, Robert Dudley. Their memorial (below left) employs multiple uses of symbolism and Tudor imagery. Lettice would have been careful to use symbols and imagery that were discreet and could be interpreted in several ways, similar to her red rose imagery in her Gower widow’s portrait. For example, the white flowers (below top right) that are carved throughout the memorial. Traditional heraldic analysis often defaults to the “cinquefoil” because of the Dudley family’s official claims to the Warwick earldom. However, recall that cinquefoils are a type of rose, and I believe Lettice chose this particular floral motif because it could be interpreted as cinquefoils or white roses, a nod to her York ancestry, an ingenious way to double-entendre. It has been suggested these flowers could be forget-me-nots, but that cannot be the case in this example since that flower was a vibrant blue (bottom right) and shaped differently.

It should be noted that Robert Dudley used the ermine cinquefoil symbol, while the white flowers on the monument clearly are not ermine cinquefoils. Below are examples of Dudley’s use of the ermine cinquefoil, particularly on his shield (below left) in his portrait of 1563 (below right). Of all people, Lettice would have known this fact, and I do not believe Lettice would have left such an important detail out of her meticulous planning of this memorial for her beloved husband.

Another fascinating display is the red rose of Lancaster again, although this time crafted as part of the iron enclosure in front of Lettice and Dudley’s tomb (below far left and far right). These red roses are numerously displayed on the enclosure, each fashioned with five red petals, green barbs, and gold seeds in the center. It is impossible not to see the allegory here linked to other traditional symbols of the red rose of Lancaster (below second and third from the left).

Below is a wider photo of the full enclosure of their tomb.

Finally, of interest is the very top of the memorial (below). In Tudor England, placement on funerary memorials was never accidental. It functioned as a visual language that contemporaries could “read,” conveying hierarchy, kinship, and favor. Vertical hierarchy equaled importance, defining the identity and legitimacy of the person(s) commemorated below. In this case, in the center, there appears to be the Leicester cinquefoil that could perhaps also be considered a symbolic abstract Tudor rose, and on top of that, what appears to be a red rosette, its unique placement unmistakable. As if Lettice was stating “here lies a Tudor and Leicester”.

In late sixteenth-century England, the red rose of Lancaster—frequently rendered in funerary art as a stylized rosette rather than a fully naturalistic rose—functioned as a dynastic symbol referencing descent from or association with the Lancastrian royal line. Within funerary monuments, such motifs carried commemorative and genealogical meaning rather than mere ornamentation.

The rosette served as a heraldically discreet substitute for explicit royal arms or badges. This was particularly relevant for families with acknowledged or rumored royal blood, where formal heraldic claims were legally restricted or politically sensitive, as was the case for the Carey and Knollys families.

Lettice commissioned Dudley’s tomb and their joint monument, which took many years and considerable expense to build, and which she surely helped oversee and design. Obviously, the imagery and symbolism do not constitute proof of Lancastrian/Tudor descent. Yet their repeated and prominent use on the Dudley-Knollys’s monument supports interpretation within a broader pattern of constrained symbolic self-representation consistent with families who believed they had unacknowledged Tudor blood. Taken together, the red rose symbolism in Lettice’s widow portrait and the parallel imagery employed on her and Dudley’s funerary monument indicate a deliberate effort to assert her Tudor identity and to signal her descent as a granddaughter of King Henry VIII to future generations.

Leave a comment